- Home

- Swarthout, Glendon

The Old Colts Page 6

The Old Colts Read online

Page 6

“An investment!” responds Bat with a wicked wink. “What pippins!”

He withdraws, pops a cork, pours, and says to Helen, “But I will say this—there’s twenty-three notches on my gun.”

“Oooh, I’d love to see your gun!”

A droplet of melted butter rolls entrancingly into Juliet’s cleavage.

“People want to buy it all the time.”

“Buy it!”

“It’s a collector’s item.”

“I read all about what happened in Tombstone, Arizona,” Juliet informs Wyatt. “You know, you and your brothers up against those terrible men.”

“Doc Holiday was there, too.”

“What a battle that must have been!”

“It was O.K.,” says Wyatt modestly.

They have annihilated the lobsters now, and are applying napkins prodigally while Bat pops the cork of the sixth bottle of Mumm’s and pours.

“Yes, you must see my pistol,” says he to Helen. “It’s a very historical weapon.”

Her upper lip still shimmers butter.

“Do you ever fire it any more?”

“Are you girls married?” Wyatt asks Juliet.

“Well, yes. But our husbands are in vaudeville—on the Pantages circuit. They’re in Boston this week. I think.”

Bat lights Helen’s cigarette, which raises Wyatt’s eyebrows. “Of course I fire it, my dear—whenever I can.”

Juliet’s hand is on Wyatt’s knee.

“Vaudeville, you say.” Bat takes an interest in all things theatrical. “What do they do?”

“Well, my husband is ‘Beppo, the Sicilian Strongman,’” says Helen proudly. “He tears catalogues in two and bends iron bars with his bare hands.”

Bat’s hand is on Helen’s thigh.

“Really?” Wyatt has always taken an interest in feats of strength.

An arm parts the curtains and extends a menu and a pencil for Mr. Masterson’s autograph, which he provides.

“My husband has a dog act—’Carl’s Canines,’” says Juliet. “They’re the darlingest dogs!”

“Would they fight a badger?” asks Bat.

“The Buffalo Wallow?” asks Juliet, having thought about it.

“Two Indian wives!” exclaims Helen.

“Where do you girls hang your hats?” Wyatt inquires, his hand on Juliet’s knee.

“We share an apartment in the West 50’s,” Helen confides.

A waiter’s arm presents the bill, which Bat scans and requests a pencil.

“Would you like to see it?” Juliet suggests.

Instead of providing a pencil, the arm summons Bat beyond the curtains.

“Sure would,” says Wyatt.

“Mr. Masterson, sir, sorry, but you can’t sign,” says the waiter.

“D’you know who I am?”

“I’m sorry, sir.”

“Send George Rector over here.”

“He’s the one said so, Mr. Masterson. He says you pay up your whole bill from before, he’ll run you another one.”

Bat asks Wyatt to step outside the booth, then explains the situation. “I’m down to coffee-and-cake money. Can you take care of this?”

“How much?”

Bat hands him the bill.

“Sixty dollars and sixty cents!” Wyatt’s aghast. “All I’ve got to get home on is a hundred-fifty!”

“You want to wash dishes?”

Wyatt pays up, adding after deliberation a dollar tip as Bat orders the waiter to inform George that, hoity-toity or not, a saloon is a saloon, and he will never patronize this one again.

Exeunt all, W.B. Masterson with lip curled, W.B.S. Earp in considerable dudgeon, and the Ginger Sisters in some disarray, their roses buttered, their ostrich plumes damped with Mumm’s and drooping, their gold mesh snoods garnished with lobster shell.

Only to discover, as their hansom clops to a stop before an apartment house on West 58th, that their driver is Gas-House Sam, a notorious gyp, and that his price for the transportation is ten dollars.

“Ten dollars!” Wyatt barks. “Highway robbery!”

The horse retorts a Bronx cheer.

The Ginger Sisters giggle and sway up the steps, leaving a trail of rose petals.

“Two miles, ten bucks,” says the hackie.

“You detoured us through Central Park!” accuses Bat.

Sam is adamant. “Ten bucks or I call a cop.”

Bat takes Wyatt aside. “Pay ‘im. I’ll pay you back tomorrow. I told you, all this is an investment—in a few minutes the fun starts, and it’ll be worth every cent, I guarantee it, pal. You ain’t saddled up a big-city baby, you ain’t saddled!”

“Where the hell you been!”

This from an enormous young man with pomaded hair and a swordpoint mustache and shoulders as wide as a barn and biceps as thick as Sears-Roebuck catalogues, wearing a striped tank top and tights, who is working out with barbells.

“Why are you home!”

This from Helen, ostensibly his wife, who has opened the door to the ratty living room of an apartment which, rather than being dark and conducive to romance, blazes with light.

“We closed in Boston,” says Beppo, the Sicilian Strong-man. “Thought we’d surprise you and—”

“We sure did!”

This from a tall slim young man in a boiled shirt and riding breeches and boots who stands ring-mastering four small dogs of indeterminate breed, but probably Pomeranians, with pink bows on their heads, who dash single file and leap one after another from a footstool to a table and up through a hoop on a standard and down to run in a circle to repeat the routine.

“Who the hell are these old poops?” Carl demands of Juliet, ostensibly his wife.

The Ginger Sisters’ guests stand transfixed, mouths opening and closing like fish for air.

“Oh, these are our friends!” trills Helen. “Mr. Masterson and Mr. Earp!”

“What the hell they doing here!” growls Beppo, bending to pick up an iron bar.

“We... we... we just stopped by for a cup of... of... of cocoa!” manages Bat.

“Coffee!” Wyatt corrects.

“Coffee my ass!” cries Carl, snapping his fingers at his act.

Juliet attempts to untangle the contretemps. “You don’t understand—this is the real Bat Masterson—and the real Wyatt Earp!”

“I don’t give a shit if they’re Buffalo Bill!” says Carl, picking up a telephone. “I’m calling a lawyer! We’ll sue for alienation of affections! We’ll take ‘em for every cent they got!”

Round and round, up and over and through the hoop, Carl’s Canine’s rush and commence to bark as they sense the drama rampant in the room.

“Oh, no, you can’t do that!” yelps Bat.

“The hell I can’t!”

“We gotta keep this out of the papers!”

“Headlines!”

“Mr. Earp’s traveling incognito!”

Carl lifts the receiver from the hook.

“I’m a married man!” Wyatt protests.

“I have an aged mother!” Bat begs.

Helen and Juliet have slipped discreetly stage right into another room. Bat and Wyatt retreat toward the door.

“Get ‘em, Bep!” cries Carl.

And with a bellow not unlike that of the male elk in rut, the Sicilian Strongman crashes across the room and, before his victims can find the doorknob, rams them both against the wall with an iron bar athwart their throats, then bends the bar into a V so that they are trapped, backs to the wall, their wind cut off. They struggle, but in vain. They turn blue in the face.

“What—can—we—do?” Bat chokes.

Carl comes to them, as do his dogs. The performing Pomeranians leap up at them and loudly bark. Carl shakes his fist in their blue faces while Beppo holds them in durance vile.

“You can pay up!” Carl snarls. “Try to make time with our wives while we’re out of town, will you? Then you pay the price, you old goats! Let’s have your wallets!”

“I’m—I’m—broke!” Bat gasps.

The Sicilian Strongman growls and bends the bar across their larynxes more brutally.

Bat rolls bulging eyes at Wyatt.

“But—he’s—loaded!”

Up on the corner of Broadway and some street in the West 50’s a Salvation Army band tootled “Nearer My God To Thee” in discordant hope, even at that late hour, of lassoing lost souls and bringing them into the fold.

Catching his wind, Bat sat on the curb before the Ginger Sisters’ apartment house. Wyatt stood behind him, breathing like an old cayuse with the heaves. Noting a rose petal on the pavement, Bat picked it up and pressed it to his nostrils. He knew what was coming. It came. Wyatt stepped around him off the curb, loomed above him, took his slouch hat by the brim, and hurled it to the ground.

“Choused again, goddammit! I didn’t come to this hellhole of a town to get plucked like a damn chicken!”

“We were set up, right from the start,” gloomed Bat. “I should’ve known.”

“You sure should—you’re the city slicker! Why’d you tell ‘em I was loaded?”

“Had to,” said Bat, chin in hands. “Did you want to die in an iron necktie?”

Wyatt dusted his hat. “You’re stretching our friendship out of shape,” he warned.

Bat was thinking. “We had guns tonight, this wouldn’t have happened. I can’t figure out what’s taking the President so long.”

“Well, I’m cleaned. All I’ve got left is a return train ticket. What do we do now?”

Bat rose, rubbing his throat. “I’ll think of something— trust me.”

Wyatt put menacing hands on hips. “Bat, I don’t ever want to hear you say that again.”

Bat grasped his arm, suddenly, his attention riveted on something down the dark street. “Oh my God—look!”

Two men in leather caps. Grogan’s muscular mugs have popped up from behind a flight of steps and start for them on the run. “Cheese it!” cries Bat.

They take off together, heading for the haven of Broadway. Wyatt falters.

“Shake a leg!” puffs Bat. “What’s wrong?”

“Got a gimp knee!”

“You said your shoulder!”

“Knee, too!”

On the great gunfighters gallop, blowing and snorting, trying to get as near as they can, not to God but to the Salvation Army.

This time they were admitted to the office of the Commissioner of the NYPD on the dot. Anthony Lucca sat behind his desk, fizzing like a fuse, and pointed at the permits on the corner of his desk. Bat picked them up.

“Much obliged, Commissioner,” he smiled, passing one to Wyatt.

Lucca leaned forward and emplaced elbows on the desk and aimed two heavy-caliber fingers. “I want to tell you birds a thing or two. Mather, I don’t know who you are and couldn’t care less. But I know you, Masterson, and you listen. This is no bang-bang, birdshit cowtown thirty years ago and you’re not marshaling any more. This is New York City and this is 1916. You behave yourselves. You be in bed early, both of you. You start shooting the lights out in our saloons or scaring our barflies half to death or plugging somebody to see if you can still do it and I’ll have your ass in a Sing Sing sling.”

“Wouldn’t think of it,” smiled Bat.

“Or a museum.”

“Is that a fact?” smiled Bat.

“Or an old folks’ home.”

Bat bowed to Wyatt to precede him and, waving his permit at the Commissioner, toddled out humming “Be My Little Baby Bumble Bee.”

“Jehu,” said Wyatt. “Must be a lot of cowboys in town.”

“I buy ‘em,” said Bat. “Ten bucks a throw, any pawnshop.”

They were looking into the drawerful of Peacemakers in his desk at the Telegraph.

“Why d’you want so many?”

“I sell ‘em. These tinhorn collectors come through every week. I’ve cut twenty-three notches in the grip and I lay it on the desk and tell ‘em I won’t part with it—I pull a long face and say that was the very gun killed Walker and Wagner after they did Ed in. Well, that’s red pepper in the pee.”

“They believe it?”

“One born every minute. Take your pick.”

They laid out an assortment of iron and began hefting for balance and squinting down barrels and turning cylinders and trying trigger pull and ejector rods.

“Feels strange, don’t it, handling these old thumbbusters again,” Wyatt mused.

“Like old times.”

They grinned at each other.

“This one’ll do.” Wyatt pushed the weapon under his belt.

“I’m all set.” Bat belted his choice. “But we can’t carry ‘em this way, not in the city.”

“How, then?”

“I know—shoulder holsters. We’ll go down to Bannerman’s downtown. They’ve got a line of everything, they can fit us special. Say, you ever used a shoulder holster?”

Wyatt shook his head. “No. Some did, though. Gamblers, mostly. But Hickok did, too, now and then. He told me so.”

Bat was trying to ease the Colt out of and under his belt. It did not ease. “I must have put on a few pounds. I didn’t know you knew Hickok.”

“I didn’t, not well. But I saw a lot of him the summer of ‘71, around Market Square in K.C.—the summer before I ran into you. I was just a kid, and he showed me some things.”

Bat was interested. “You never told me. Hickok was a shooter, was he?”

“Sharp as ever I saw. I saw him drive a cork into a bottle at sixty feet. Split a bullet on the edge of a dime.”

“Tricks.”

“Try ‘em.”

Bat was piling the rest of the revolvers into his desk drawer. He winked. “Hickok couldn’t sing and dance, though.”

Wyatt was not amused. “Glad you mentioned it. I mean it, Bat, I’ve had a crawful. I didn’t come clear across this country to sing or dance or drink four-dollar champagne or allemand left with your fancy chippies. I told you, I’m down to my train ticket. If I can’t make a stake, that’s one thing, but I’m not going home in a damn barrel.”

“Stop fussing. I was worried about Grogan, that’s all. Now I’m not. Now we’ve got guns, we’ll get the money.”

“Easy said. But where do we go from here?”

“Bannerman’s. Let’s ride.”

Bat had hold of the doorknob when Wyatt said, “Wait a minute. You recollect Doc Holliday?”

“Sure.”

“He was a lunger, you know—died in Colorado. I heard he asked for a glass of whiskey and drank it down. Then he said, ‘This is funny,’ and cashed in.”

“So?”

“Well, that’s funny, too, what you just said. Stop to think about it, that’s the way it was back then. Still is, I guess.”

“What?”

“Guns first, then the money.”

They buttoned jackets over the pistols under their belts and left the newsroom and were passing through the reception area of the paper when Bat was pointed out by a clerk to, and accosted by, a matronly dame with a kid in tow.

“Oh, Mr. Masterson!” she gushed. “This is my son Wayerly—he’d be thrilled to meet you!”

They stopped, Bat to offer a man’s hand to the kid. “Howdy-do, Waverly.”

Waverly might have been twelve, had an evil eye, and a hand fresh out of the Fulton Fish Market.

“Would you give him your autograph, Mr. Masterson?” implored the dame. “He’d be thrilled!”

She provided paper, Bat his Parker, and while signing was put this question by the kid: “Did you really kill thirty-six men?”

Bat finished “W.B. Masterson” with a flourish, looked gravely at the kid, and lowered his voice. “Forty-six,” he confided.

“Horsefeathers,” said Waverly.

“Oh, thank you, thank you!” shrilled his ma, snatching the paper before the ink was dry. “We’re ever, ever so grateful, aren’t we, Waverly?”

“Aw, he’s old,” s

aid the kid.

“My pleasure, ma’am,” said Bat, tipping his hat and fighting the temptation to cauliflower the little turd’s ear, and moving on with Wyatt.

They had just reached the front door when the room rang with a loud bang.

Mssrs. Earp and Masterson whirled, fumbling under jackets and hauling away at Peacemakers until, faces red as lobsters, they identified the cap-pistol Waverly waved at them.

“Har! Har! Har!” sniggered the squirt.

Wyatt wanted to walk to Bannerman’s, which was located on lower Broadway at 10th Street. Bat was aghast. Walk forty blocks? Wyatt reminded him of his offer to show him, Wyatt, the sights. Bat suggested the subway, which had just been completed to downtown Manhattan, arguing that every out-of-towner must ride a subway. Wyatt reminded him that he had never hunted a hole in his, Wyatt’s, life and was not about to. Bat suggested the Fifth Avenue bus, transport aboard which was available for ten cents. Wyatt reminded him that he, Wyatt, was broke. Bat suggested the nickel trolley car. Wyatt’s response was in the negative. Bat suggested that a hike practically to the Panama Canal would be bad for his, Wyatt’s, gimp knee. Wyatt reminded him that walking would be good for his, Bat’s, cold feet and circulatory problems. Backed into a corner, Bat suggested they take a taxi, offering to pay the shot himself. Wyatt said Bat could ride and he would take shank’s mare. He was an outdoors man and needed exercise and so, by all indications, did Bat, who was getting slow as a cow with a full bag. They looked hard at each other. Bat recalled: when Wyatt made up his mind on a matter, he was adamant as a Missouri mule. Wyatt recalled: Bat had always been as slippery as a hoop snake. Try to pin him down and he would slither this way and slather that and eventually stick his tail in his mouth and roll away out of sight. Bat suggested they toss a coin. Wyatt reminded him of his luck of late. Bat spat and got out a penny.

They hoofed the forty blocks, Bat on condition that they use a public conveyance on the return. The day was late April and lovely. Acting as guide, Bat pointed out to the tourist a variety of metropolitan attractions. Women beautiful enough to knock your eyes out, and gussied up in the height of fashion. Gents dressed ditto: The giant electric signs around Times Square advertising Uneeda Biscuits and C & C Ginger Ale and Studebaker autos. Streetsweepers in white uniforms picking roadapples. The Metropole Hotel, gone but not forgotten, in front of which Herman Rosenthal, the gambler-gangster, was mowed down, and for whose murder five men including a police lieutenant were fried in the electric chair. The choke of two-way traffic, a motley of hansom cabs, carriages, and bicycles, but mainly gas-powered now, sedans and touring cars and limousines and open-top buses. Policemen directing that traffic at the centers of intersections. A moving picture house showing “Hell’s Hinges,” the latest starring vehicle of Bat’s pal William S. Hart. The green trees of Union Square. So-called “skyscrapers”— the Flatiron, the Metropolitan Life, the Singer, the Woolworth, etc. Saloons with side doors through which you could slip, if perishing of thirst, on Sundays. And finally, as they got downtown, the streets torn up to replace cobblestones with Belgian blocks.

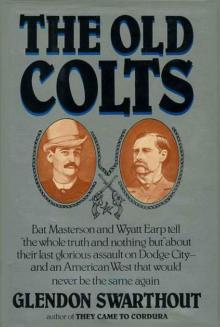

The Old Colts

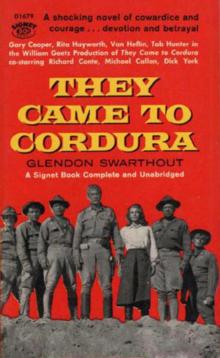

The Old Colts They Came To Cordura

They Came To Cordura