- Home

- Swarthout, Glendon

They Came To Cordura Page 2

They Came To Cordura Read online

Page 2

“I see. You believe we will enter the war, then?”

“If you know how we can stay out, tell me.”

“That’s the only reason?”

“The principal. This also is the last cavalry campaign any of us will see. What General Sheridan started, General Motors is going to finish.”

Time dragged. The wind fisted the touring car. Once the General’s aide came, a handkerchief muffling his face, and a door on the lee side of the car was opened upon a premature night in which the entire regiment, men and animals, was swallowed up by airstreams of sand.

“General,” Emmett Harris said, “this ranch where you’re sending Rogers—did I understand it’s owned by a woman named Geary?”

“I suppose it’s the ranch Senator Geary owned.”

“Senator? Adolf Geary?”

“I know he owned one.”

“Jesu.” Harris sat up. “Then that’s his daughter; that’s where she’s hidden. Don’t you remember, Geary died in ‘o8 and she disappeared the same year? She has been there out of sight for eight years. What opulent irony. Instead of Villa, the U.S. Cavalry catches up with Adelaide Geary. I didn’t connect the names.” Harris coughed violently.

“I may have heard of her,” Pershing said. “I was in the Philippines then.”

“You would have even there.” The newspaperman filled him in. A member of the Indian Affairs Committee, a man of great wealth and long tenure in the Senate, Adolf Geary of Missouri had been convicted of fraud in connection with the sale of reservation lands in 1908, dying that year in prison. It had required considerable time and moral ingenuity (the term Harris applied), for his daughter to equal his disrepute, but this she had managed to do. “The delicious part being,” he concluded, “that it was all true about her. A woman more sinning than sinned against.”

“If she’s the one,” the General said.

Using a small silver nail-cutter the Tribune man began to trim his nails, dropping each cutting carefully to the car floor. “Adelaide Geary,” he said. “What a stroke of luck.” He examined the trimmed nails, fingers extended. “Incidentally, isn’t there something stuffy in the Constitution about a citizen giving aid and comfort to an enemy of the United States? Something to that effect?”

“It would be a fine point to establish. We are not at war with Mexico.’’

“Unfortunate. I must look into it, though. What a lark it would be to haul her kicking and screaming back across the border. Exclusive interviews from the El Paso pokey, that sort of thing.”

The afternoon wore itself out. The wind did not abate. The stiffened isinglass of the side-curtains crackled.

“Gibbons asked if you thought you would capture Villa, General, and you turned him off with a joke. Perhaps it’s a stupid question, but do you think you can?”

Pershing sat in the corner of the seat, erect, his eyes closed. Except for his posture, he might have been asleep.

“Harris,” he said after a time, “understand something. When I talk to you this way, it is one person to another, nothing more. If you put what I say in your dispatches, I will cut it out. Now your question: do I think I can catch Villa? No, I don’t. He knows Chihuahua better than I do and he can live off it. I have a front seventy miles wide and practically no communications. Even so, I feel sorry for him. He has lost a lot lately, as I have.”

It was dark in the tonneau. The correspondent could scarcely see the spare, sharp-boned face of the commander. The mouth was a straight line. Over it a moustache had begun to grey. Hooking down to the corner of the mouth a furrow cut deep in each cheek. The allusion to loss puzzled the correspondent until he recalled the tragedy of the year before: by telephone the General had been informed that his wife and three young daughters had lost their lives at San Francisco in a fire which had destroyed their quarters; only the infant son had survived.

Emmett Harris changed the subject. “By the way, how exactly does an Awards Officer function? I see him galloping about the country looking for battles and bravery, then writing it all down in deathless prose.”

“His duty is to find men who deserve recognition. He writes a citation, signs it and swears to it as an officer. Then I and the Chief of Staff of the Army and the Secretary of War must endorse it. Congress will generally approve what we endorse.”

“Remarkable,” Emmett Harris said. “If you don’t mind, I’ll do the first story on him.”

“I do mind,” John Pershing said.

“You do?”

“I do.”

“But he’s a hero-maker, General, a Homer on horseback. Or a Virgil—arms and the man he sings!” The correspondent flung up a plump hand in mock salute.

“Harris, I said no.”

The New York Tribune man was caught in mid-salute. The General’s words, direct as though delivered to a child, were less a statement than an order. Awkwardly Emmett Harris lowered the hand, leaned back. He was stunned. In some way he had given offence or stepped upon forbidden ground, and for it he had been rebuked. He could not allow this situation to firm. Opening the door of the Dodge he closed his eyes and went through the storm to the rear of the car to search blindly in the luggage strapped beside the spare wheel as the sand scoured the skin of his face and the wind blew his new hat from his head and brought him to his hands and knees so that he tipped over a water-can. Hating the wind and the country and what he was about to do, he thought: ‘You are a city man and live in a flat and you are afraid of this general; if you had been in the soldier Hetherington’s place you would have run for your life because you are probably a coward.’ Then coughing, spitting, hatless, he returned with a large pre-baked ham he had intended to save for himself.

“Here we are, General, with my compliments,” he forced himself to say. “We will starve before morning.”

“Well, look here.” John Pershing opened a pocketknife. “I will have a little, thank you, Harris. We must take back most of it to the others, though.”

They ate.

Chapter Two

WITH the fall of night the wind fell, suddenly. Sand, for the first time in hours, ceased to blow. Officer and enlisted man stopped amid a great hush. The absence of sound seemed in itself a terrifying fact. The stars were shrouded. Their throats sore from breathing through their mouths, the two men blew filthy strings of mucous dust from their nostrils and then, each wrapped in a blanket, they rode on while sand grains, held high by the storm, filtered endlessly down through darkness, touching like the tips of unseen fingers their bared faces. They talked. There had been no opportunity since the morning’s fight at Guerrero for Major Thorn to find out anything about the enlisted man, Hetherington. Neither had he told him why he was detached from L Troop for temporary duty; he would have to choose the right time for that. Now, as they rode, he learned that the private’s name was Andrew, he was twenty-three, his home was a town in Kansas called Dancey. He had no brothers or sisters. Two years ago he had enlisted without telling his parents, being assigned to the 6th Cavalry stationed then at Fort Huachuca, Arizona.

The youth responded freely to questions, answering in a drawly Kansas voice over the edge of his blanket. He seemed grateful that an officer of such high rank should take an interest in him. When asked about his parents, however, he spoke hesitantly, of his father with hatred, of his mother with longing.

His father was an itinerant preacher, a minister in ‘The Sole Church of Christ Resurrected’, an evangelist who travelled most of each year from country church to country church over Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado, stopping from three days to a week to put on revivals, percenting the collections with the local parson. He played the trombone, his wife the piano. They sang duets. This had been Hetherington’s boyhood and adolescence: constant movement, infrequent schooling, as he grew older regular resistance to, then surrender before, the emotionalism of the revival. He had himself taken part in the show. Almost from infancy he had been taught the Bible by his father, it being his weekly task to memorize one chapter, verse by v

erse. Before he could read he had learned by heart the Pentateuch. By age eight he appeared nightly, introduced as a prodigy by his father, who challenged the congregation to stump him by calling out book, chapter and verse. At each call he recited. By age eighteen he had committed all thirty-nine books of the Old Testament to memory. The Good Book, he said, had been beaten into him.

Their way, during the long afternoon of storm and later, in absolute darkness, lay for the most part eastward over grass plateaus. There was no proof of trail except the soft footfall of the weary horses in dust and now and then the grate of pebble against shoe. The officer estimated they had come twenty miles from Guerrero; he intended to push on another five if the animals held up. He was glad to have the youth talk. His voice made company for them both. The night grew piercing cold. Differences of fifty degrees in temperature between noon and midnight were not unusual for this time of year.

Hetherington said he had balked at beginning to learn the New Testament. He had come to blows with his father. Then one day, while the family was passing through Oklahoma City, he had slipped away to enlist.

“How did you happen to?”

“I saw an Army poster, Major, and got the notion all at once. I couldn’t stand it any longer anyways. It was like I was carrying a cannon ball in my head. I used to have lots of headaches from it. Besides, I didn’t have the faith anymore.’’

“The faith?”

“I couldn’t believe. I knew most of it wasn’t true. Then at night, in the meetin’s, I would re-cite a while and the folks would holler and roll on the floor and carry on and I would start to cry and believe it even when I knew it wasn’t true. Then in the morning I’d be ashamed. I was too big to cry and carry on. I’d swear I wouldn’t let it happen the next night but it always did. So finally I enlisted. I write to my ma but she don’t answer. He must not let her.”

The officer said nothing. The youth’s flight had been from the terrible Jehovah that was his father to the more impersonal power that was the Army’s.

“Have you forgotten it all now?”

“That’s the worst part, no, sir, I haven’t. I thought I would in the Army but sometimes in the morning I wake up and can tell I’ve been at it in my sleep. I’m not rested any. I did it out loud once, too, when me and some buddies went to Phoenix and they got me drunk. It’s been two years and I haven’t forgot a word.” Hetherington cleared his throat. “I’d just as soon re-cite for you, Major.”

“I don’t know the Bible very well.”

“You don’t have to, sir. Just tell me a place.”

“Well, all right. Aren’t there some genealogies, with begats and so forth?”

“Sure, like Genesis 11.12. ‘And Ar-phaxad lived five and thirty years, and begat Salah: and Ar-phaxad lived after he begat Salah four hundred and three years, and begat sons and daughters. And Salah lived thirty years, and begat Eber: and Salah lived after he begat Eber four hundred and three years, and begat sons and daughters. And Eber lived four and thirty years, and begat Peleg’—that’s too easy, though. Here’s one harder, Numbers 33.28. ‘And they removed from Tarah, and pitched in Mithcah. And they went from Mithcah, and pitched in Hash-monah. And they departed from Hash-monah, and encamped at Mo-seroth. And they departed from Mo-seroth, and encamped at E-bronah. And they departed from E-bronah, and encamped at Ezi-on-gaber. And they removed from Ezion-gaber, and pitched in the wilderness of Zin, which is Kadesh.’”

It came out of Hetherington without effort and without understanding; the place names, mispronounced, came out endlessly in the flat Kansas monotone. The Major heard pride, though, and fear. ‘Re-citation’ was probably the young trooper’s only accomplishment, but each meaningless phrase was also a reminder of his own disbelief, that godlessness which frightened him. The Major let him continue.

“‘And they removed from Almon-dibla-thaim, and pitched in the mountains of Aba-rim, before Nebo. And they departed from the mountains of Aba-rim, and pitched in the plains of Moab by Jordan near Jericho. And they pitched…’”

“Wait,” the officer interrupted. He was staring to the left, where loomed a blackness more stark than the night. Halted, they could tell the outlines of a butte, a mass of rock upthrust and solitary on the plain, tablet-topped, a hundred feet high, a monument to nothing.

“We’d better stop here. Can’t be more than five miles to Trias. Tomorrow may be hard on the animals.”

They rode to the base of the butte and dismounted. While the private unsaddled the horses, Major Thorn built a fire with dry twigs of the encino tree. The wood snapped, flared, and light reached up the wall of rock. Hetherington had no grain and the officer offered to share the last of his corn so that both animals might have one more feed. Spreading a blanket he poured the grain on to it and showed the trooper how to pick out the little pebbles found in native corn, for once a horse bit a stone he would not eat. Forage for the Expedition was always in short supply; used to oats and hay, the animals took slowly to corn, which weakened them; on grass, which would be brittle and poor until the rains of spring commenced, they became so hungry that they chewed their halter shanks incessantly, rope or leather. After swabbing sand from the nostrils of the horses with damp rags the two men rubbed them down and put on the nose-bags. The Major’s personal mount, a pure-bred Morgan he had bought in garrison and learned to love, had died of colic during the second week of campaign, and he had been supplied with a remount at Dublán, a big chestnut eight years old, too high and loose of build for hard service. He watched it feed. He could not develop affection for it. Already it had lost much flesh and seemed twelve years old, appearing ‘roady’ about the knees and hocks; the cavities above the eyes had deepened and the head had an aged look. The tail was limp. He called the animal ‘Sheep’. He thought that a good name for it.

Nose-bags were taken off and the horses hobbled with rawhide manejas removed from the necks, passed around one foreleg, twisted, buttoned around the other foreleg. Only then did the men attend to their own wants. Hetherington’s eyes were sore and inflamed from dust and the officer found some boric acid in his saddlebags and washed them out. They heated hard bread over the fire and made coffee. Hetherington’s cup, which was the new aluminium, had melted through, and since the officer’s was the old tin issue and thus intact, both drank from it. When they had finished, the Major suggested they clean their weapons, since they must be full of sand, so each found oil and patches and brought the Springfield rifle from his saddle boot. Blankets about their shoulders, their backs to the butte, they sat close to the small fire in position, as it were, to defend themselves against the still and limitless dark which closed in on them. Neither could now remember the wail of the afternoon wind.

“It sure is cold,” Hetherington said. “It gets in your bones at night and stays there all day. The rest of you burns up but your bones stays cold.”

He was a tall, gangling youth with knuckly hands, large feet, a high forehead with prominent frontal bones. His hair, was flax-colored and straight. The stubble on his cheeks and chin was sparse. The length of his head, the serious, almost aged expression about the eyes reminded the Major of his remount, Sheep. Hetherington was not in any way soldierly: the officer had noticed his awkward seat mounted, and noticed now that the sole of one large shoe was loose, exposing a torn sock and one bare, grimy toe. With the rifle his hands were clumsy.

“It’s a funny thing, but it sure seems like a long way from home down here, from the States I mean, don’t it, Major?”

“Yes, it does.”

“Are you married and with a family, Major?”

The youth was trying to make conversation, and the officer, wondering how to interview him, what questions to ask, how, above all, it had come to pass with such a one as this, he did not know what to talk about. Propping the rifle against the rock, he took his pistol from its flap-holster on his right leg and removing the magazine began to clean the weapon. Tending to jam when dirty, entirely dependent on the magazine which, damaged or

lost, made the pistol inoperable, the .45 automatic had been found on the campaign to be unsatisfactory, a weapon of two parts, where the older Colt revolver had been one-part. Hetherington saw him clean his pistol and followed suit.

“Sir, I haven’t talked to anybody yet who was at Columbus. We all heard it was pretty bad, though.”

“They did surprise us,” Major Thorn said. This was a thing which could be talked about if he were cautious; which had to be, in fact, sooner or later. Working slowly on the pistol, he described how the Villistas had come in the night, tearing into the little town mounted, burning up thousands of rounds of ammunition, setting fires; how Colonel Rogers’s colored butler crawled under the Colonel’s bathtub, which cleared the floor by only six inches, and remained there until dawn; how the confused, sleep-slowed troopers of the 12th Cavalry fought in unofficered bunches out of barracks and stables; how the cook crews held the kitchen shack with axes and boiling water; how Mrs. Gardner, strapping wife of the regimental adjutant, hid with her daughter in the mesquite behind her house and with a carving knife cut the throat of a Mexican who found them; how a trooper in the stables killed another with a baseball bat; how one group of enemy were caught against the adobe wall of a mess shack by a machine-gun firing low to get advantage of ricochet and were cut to bits, literally, so that the next day pieces of skull as large as a hand, with the long hair of the Yaqui Indian attached, could be found; how ninety-one bullet-holes were later counted in a car parked before the Bank of Columbus; how officers, quartered with their families in houses at the edge of town, finally reached their commands and after an hour and a half of fighting, by the flames of the Commercial Hotel and the U.S. Post Office, forced the Villistas south into the desert, maintaining daylight pursuit several miles across the international boundary.

Hetherington sat wide-eyed. It seemed as good a time as any. Holstering the pistol and returning the Springfield to its boot, Major Thorn sat down again and took from his shirt pocket a small black-leather notebook and the stub of a pencil.

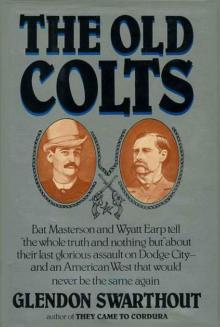

The Old Colts

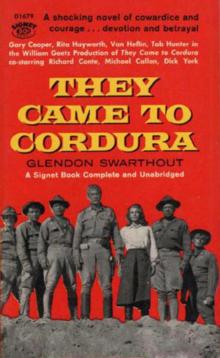

The Old Colts They Came To Cordura

They Came To Cordura